In society’s terms, it’s called “fight or flight.” In the courtroom, it’s discussed as Duty to Retreat or Castle Doctrine. In reality, it is knowing when to use deadly force in a situation or when not to. The lines aren’t always clear, but it is important to know the laws and how to train for these scenarios.

For today’s topic, we won’t get into the situational aspects that always need to be factored, such as how much collateral damage could the proposed deadly force do? Instead, we will consider the first moment when assessing a situation in which we decide if we are legally obligated to “retreat” or if we can apply castle doctrine (or stand-your-ground, as explained shortly).

Castle Doctrine

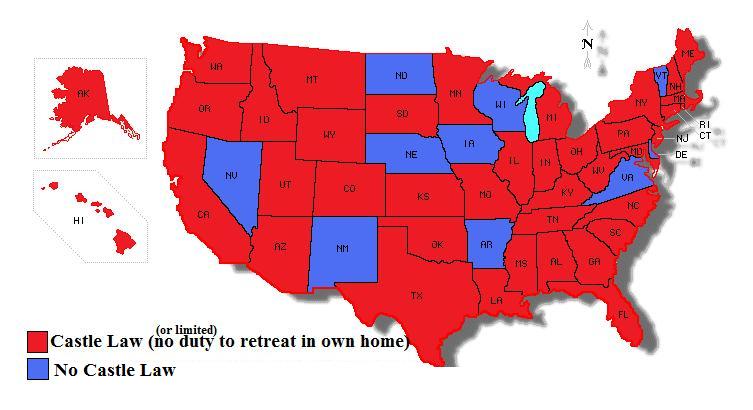

Castle doctrine, also termed castle law or defense of habitation law, is a legal doctrine applicable in 46 U.S. states that designates a person’s house, or in some states any legally occupied place (i.e. vehicle or workplace), as carrying protections and immunity against persecution to use force, up to deadly force, to defend against an intruder.

The first sticking point in regards to castle doctrine is that it is not a law; instead it is a set of principles which have been incorporated in some form of laws in different states. Therefore, at times using deadly force in relation to castle doctrine can deem the act as “justifiable homicide.”

Where castle doctrine gets even more tangled is the subjective requirement of fear.

Cases where this has been shown to be controversial include the deaths of Scottish businessman, Andres de Vries, and Japanese exchange student, Yoshihiro Hattori, the latter whom died in 1992 in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, when he went to the wrong house, accidently, trying to get to a Halloween party. He was unarmed and shot point-blank in a driveway. The property owner was subsequently acquitted in the state court of Louisiana.

To add an additional layer to castle doctrine, some states include a stand-your-ground law, in which one can use deadly force in any location one is legally allowed to be, without requiring an attempt to retreat, to defend against a threat, even outside one’s own home. In fact, 22 of the 46 states that have a castle doctrine removed the “duty to retreat” requirements from locations outside a person’s home.

Duty to Retreat

Now jump to the other side of the situation, when you have to determine whether you have a “duty to retreat.” This is a specific component that often appears in defense of self-defense. For jurisdictions that require a duty to retreat, the burden of proof is on the defendant to show that he first attempted to avoid conflict and, furthermore, took reasonable steps to retreat or displayed an intention not to fight before using force.

When, then, can one use force where the lines of “duty to retreat” and “stand-your-ground” intersect? The question is slightly rhetorical, as it is imperative that one knows the laws and principles in one’s own state. However, we can learn from how police are trained to detect situations that require deadly force and apply some of the same principles.

First, in a well-written article by Tracy Barnhart about the duties of correctional officers, he writes a great deal about fearin a situation. In some (legal) cases, fear is a requirement for self-defense. However, as Barnhart notes, fear can also overload your system and skew one’s perception of danger. Therefore, he recommends the following advice for having “reasonable fear:”

Progression of Reasonable Fear in a violent situation:

1. Perception of a threat

2. Awareness of vulnerability

3. Decisions to take action

4. Survival mode

5. Decision to respond

6. Response

For officers in training, they have to make split-second decisions to assess threats. In fact, they train for a “half-second” response to use deadly force. Studies have literally measured this out, citing it takes .25 seconds for an officer to recognize a threat, such as when a person is reaching for a gun, and another .25 seconds for that officer to draw his gun. Then it takes another .06 seconds to pull the trigger.

What they practice learning is all about the hands. It’s the hands of an intruder or suspect that will hurt or kill them or others. If someone is reaching for a gun, the officer has to start making a choice.

There is logic behind this. Body language is hard to decipher. Mind-reading is out. But using the above progression of “reasonable fear,” knowing your local laws, and watching people’s hands will help you know when to retreat and when to draw.

Resources

State’s with Castle Doctrine, and the text of each law, via Wikipedia.

“Stand Your Ground” Policy Summary.

Worst Case Scenario “Deadly Force” by Tracy Barnhart.

Author: Ryan Newhouse